Cari MacLean

- Share This Story

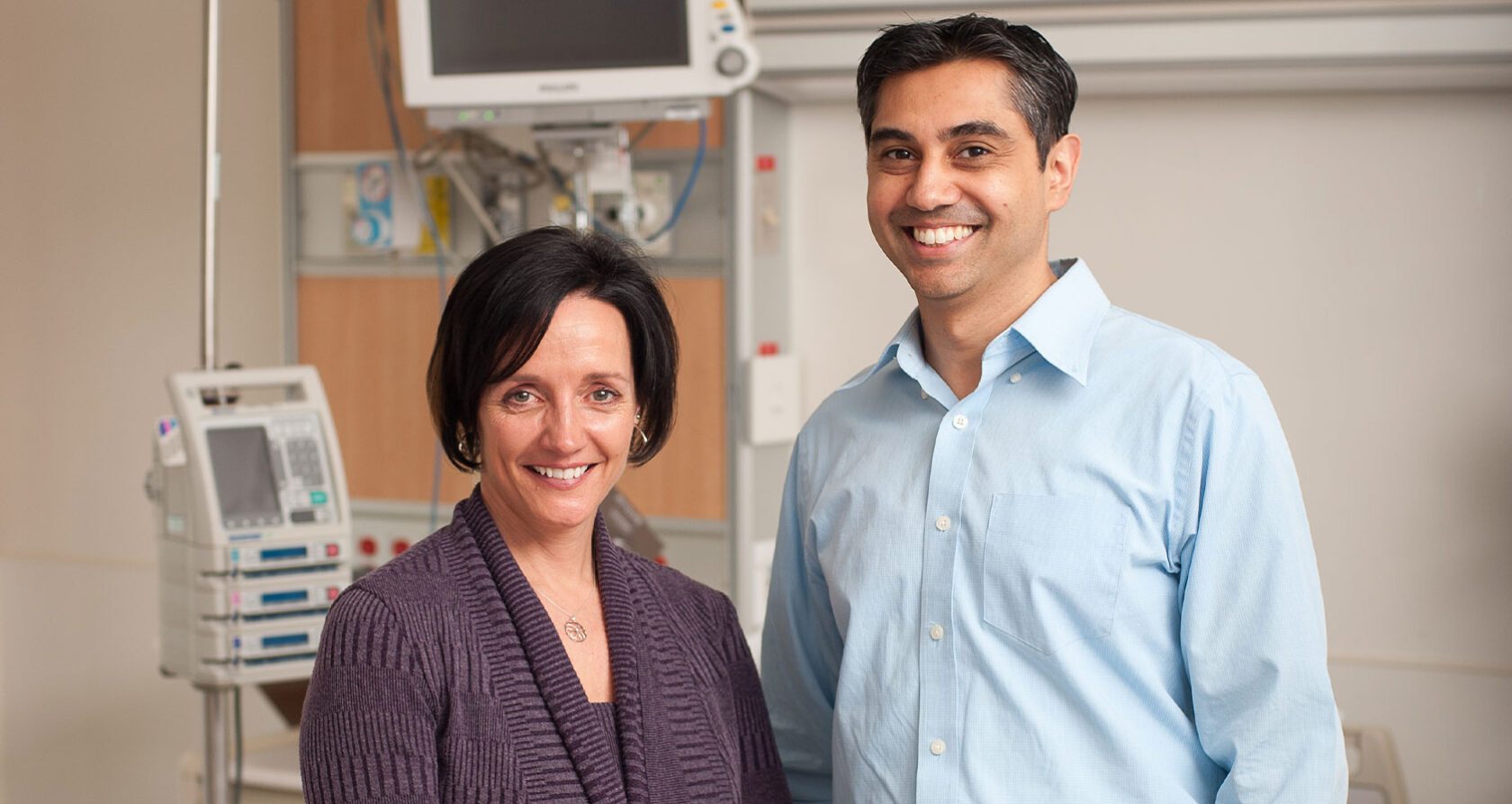

Cari MacLean will always be grateful to the staff of Oakville Trafalgar Memorial Hospital for giving her another chance.

The life of the Oakville resident, the wife of longtime Hockey Night In Canada anchor Ron MacLean, was saved last fall by a responsive emergency team, a quick-thinking doctor and a specialty ultrasound machine that had been recently purchased through a donation by former Oakville Hospital Foundation board member John Platt and his family.

Minutes after MacLean arrived at the hospital, Dr. Mangesh Inamdar was able to determine that she had a massive pulmonary embolism, a condition when a main artery of the lung or one of its branches is blocked by a substance — most often a blood clot — that has travelled from elsewhere in the body.

MacLean, who arrived at the hospital with a blood pressure reading of 30/5, no pulse and no vital signs, believes she would have been dead within an hour if it weren’t for Dr. Inamdar’s efficient diagnosis.

“I would do anything for that set of doctors, that set of nurses, that hospital, the (emergency medical technician) people,” MacLean said. “I would do anything.”

In the days leading up to that fateful day, MacLean hadn’t been feeling well. She had been experiencing shortness of breath — to the point of not being able to walk up or down the stairs in her house without having to stop — and had noticed cramping in her left calf.

Cramps in her leg were nothing new for MacLean, an avid marathon runner. And she attributed the shortness of breath to either being out of shape (“I had a pretty crazy summer,” she said) or a possible respiratory virus.

MacLean saw her athletic therapist and mentioned the cramping and also described her trouble breathing. The therapist suggested trying to work out the cramps with a warm bath, some stretching and ice. And if MacLean’s breathing issues didn’t go away, the therapist suggested, she should check into the hospital’s emergency ward rather than waiting for her appointment with her general practitioner later in the week.

MacLean went home and texted one of her women’s hockey teammates that she wouldn’t make that night’s game. Ron, meanwhile, had a men’s league game that night at Canlan Ice Sports. He left the house at 6:30 p.m., knowing that Cari could reach him on his Blackberry if she ended up going to the emergency room. Cari went upstairs and had a bath.

In the middle of that bath, she began to vomit. MacLean got out and looked in the mirror and noticed she was “ghostly white” and sweating profusely. All she wanted to do was lie down.

So that’s what MacLean did, surrounding the toilet with a nest of towels.

Then, in a phenomenon MacLean said she couldn’t explain, a loud voice broke through the chaos and panic running through her mind.

‘No! This is not how it ends! Get up off the floor!’ the voice boomed.

MacLean did, summoning the strength to lift herself up off the floor and put on a shirt before crawling down the stairs to the cell phone she had used to text her teammate earlier. She called 911.

Shortly after she made the call (MacLean said she doesn’t know how much time elapsed, but knows it wasn’t very long), six Oakville firefighters burst through the front door of her home. MacLean was quickly whisked away to the hospital.

By the time she arrived at OTMH, she was close to death.

“My heart never did stop, but they were prepared for it,” she said. “The emergency doctor was anticipating it, and they couldn’t believe it didn’t stop.”

When patients come into the hospital without showing vital signs, MacLean said, there are typically five things doctors look for and begin ruling out. But, for a variety of reasons, it was impossible for Dr. Inamdar to rule out anything.

MacLean did not show the typical signs of pulmonary embolism. The calves of her legs were symmetrical, while pulmonary embolism typically features heavy swelling in one calf. And she wasn’t feeling severe pain when breathing.

A low oxygen level would also be an indicator of pulmonary embolism. The ideal way to measure oxygen levels is through the fingernails, but MacLean was wearing nail polish that were very difficult to remove.

Dr. Inamdar considered inserting a small needle into the artery of the wrist and then analyzing the results. But MacLean’s blood pressure was so low that she didn’t even have a palpable pulse.

The doctor then checked MacLean’s oxygen level in her ear lobe. But those readings are often inaccurate, and the reading he got was “almost at a level that it wouldn’t be compatible with human life.”

Emergency medicine, Dr. Inamdar said, can occasionally force physicians to make an educated guess. That wasn’t an option in this case, however. The standard treatment for a pulmonary embolism is the use of a thrombolytic, a drug that thins out blood clots and limits tissue damage. But if MacLean had a ruptured aorta or was suffering from some other form of internal bleeding, not allowing the blood to clot would almost certainly prove fatal.

“I remember looking at her and thinking, ‘This lady is going to die, and I don’t have a diagnosis,’” Dr. Inamdar said.

At this point, the doctor turned to an ultrasound machine. After determining MacLean had no bleeding in her belly, he scanned her heart — and found her right ventricle was much larger than her left. Typically, it’s the other way around.

“Out of all the possibilities, you would only see that in (pulmonary embolism),” Dr. Inamdar said. “After doing the ultrasound, I gave her the thrombolytic medication to dissolve the blood clot. I was almost hanging my hat on that.”

Within 10 minutes, MacLean’s blood pressure and oxygen levels had noticeably improved. Shortly after that, she began to regain full consciousness.

I think we were almost cheering, because in the end we knew it was the right diagnosis,” Dr. Inamdar said. “And a lady we were fairly convinced was going to die was turning around and improving.

In the meantime, Ron had arrived at OTMH and was in the background of the operating room. He had been alerted to Cari’s dire situation by two Oakville firefighters from Fire Station 2, which is located on Cornwall Rd. — directly across from the quad-pad arena where Ron was playing hockey that night.

“It’s funny, because they just walked in and asked people if they knew what rink Ron MacLean was playing on,” Cari said. “Ron saw the firefighters come over to (his team’s) bench but he just assumed one of his guys was having heart issues. There are a couple older guys on his team… he didn’t realize they were coming to get him.

“When Ron was driving over (to the hospital), he thought, ‘Well, good, Cari must have decided to go into emergency,’” Cari added. “Then he thought, ‘Why didn’t she drive herself?’”

Cari MacLean spent two weeks at OTMH as she recovered from the ordeal.

“It was massive. My body has plenty of healing to do,” she said. “But my mind is finally prepared to face full on what happened. Before, I couldn’t go there. It was still too raw.”

During her time in the hospital, MacLean developed a great appreciation for the staff.

“They were incredible. They did not once give me any sense of panic,” MacLean said.

“They were professional. They were calm. Dr. Inamdar had control of the theatre.

“And during my stay afterwards, I saw the work environment, for the nurses particularly. It’s not an easy job, and they do it with pleasure. Not once did I feel I wasn’t been cared for.”

MacLean is not the only one who will be forever impacted by the experience. Dr. Inamdar, who said he works in emergency medicine because “it’s one of those fields where you really have this narrow window of opportunity to make decisions that change the course of people’s lives”, described the entire case Thursday as if it had happened the previous day.

“This was one of those really amazing cases,” he said.

“As physicians in general, we always keep a small group of cases in our mind. We take that with us whenever we practice, because sometimes you have good outcomes and sometimes you have bad outcomes.

“Sometimes, when you have a bad day, you look back at these cases. And it just reminds you why you do what you do.”

Together, let’s make more better care stories.

Duis nec tellus lectus. Mauris eros velit, efficitur eu scelerisque et, luctus eu leo. In quis lorem nibh. Curabitur sit amet mollis magna. Donec vitae libero posuere.